Working with missing data#

In this section, we will discuss missing (also referred to as NA) values in pandas.

Note

The choice of using NaN internally to denote missing data was largely

for simplicity and performance reasons.

Starting from pandas 1.0, some optional data types start experimenting

with a native NA scalar using a mask-based approach. See

here for more.

See the cookbook for some advanced strategies.

Values considered “missing”#

As data comes in many shapes and forms, pandas aims to be flexible with regard

to handling missing data. While NaN is the default missing value marker for

reasons of computational speed and convenience, we need to be able to easily

detect this value with data of different types: floating point, integer,

boolean, and general object. In many cases, however, the Python None will

arise and we wish to also consider that “missing” or “not available” or “NA”.

Note

If you want to consider inf and -inf to be “NA” in computations,

you can set pandas.options.mode.use_inf_as_na = True.

In [1]: df = pd.DataFrame(

...: np.random.randn(5, 3),

...: index=["a", "c", "e", "f", "h"],

...: columns=["one", "two", "three"],

...: )

...:

In [2]: df["four"] = "bar"

In [3]: df["five"] = df["one"] > 0

In [4]: df

Out[4]:

one two three four five

a 0.469112 -0.282863 -1.509059 bar True

c -1.135632 1.212112 -0.173215 bar False

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849 bar True

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804 bar False

h 0.721555 -0.706771 -1.039575 bar True

In [5]: df2 = df.reindex(["a", "b", "c", "d", "e", "f", "g", "h"])

In [6]: df2

Out[6]:

one two three four five

a 0.469112 -0.282863 -1.509059 bar True

b NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN

c -1.135632 1.212112 -0.173215 bar False

d NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849 bar True

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804 bar False

g NaN NaN NaN NaN NaN

h 0.721555 -0.706771 -1.039575 bar True

To make detecting missing values easier (and across different array dtypes),

pandas provides the isna() and

notna() functions, which are also methods on

Series and DataFrame objects:

In [7]: df2["one"]

Out[7]:

a 0.469112

b NaN

c -1.135632

d NaN

e 0.119209

f -2.104569

g NaN

h 0.721555

Name: one, dtype: float64

In [8]: pd.isna(df2["one"])

Out[8]:

a False

b True

c False

d True

e False

f False

g True

h False

Name: one, dtype: bool

In [9]: df2["four"].notna()

Out[9]:

a True

b False

c True

d False

e True

f True

g False

h True

Name: four, dtype: bool

In [10]: df2.isna()

Out[10]:

one two three four five

a False False False False False

b True True True True True

c False False False False False

d True True True True True

e False False False False False

f False False False False False

g True True True True True

h False False False False False

Warning

One has to be mindful that in Python (and NumPy), the nan's don’t compare equal, but None's do.

Note that pandas/NumPy uses the fact that np.nan != np.nan, and treats None like np.nan.

In [11]: None == None # noqa: E711

Out[11]: True

In [12]: np.nan == np.nan

Out[12]: False

So as compared to above, a scalar equality comparison versus a None/np.nan doesn’t provide useful information.

In [13]: df2["one"] == np.nan

Out[13]:

a False

b False

c False

d False

e False

f False

g False

h False

Name: one, dtype: bool

Integer dtypes and missing data#

Because NaN is a float, a column of integers with even one missing values

is cast to floating-point dtype (see Support for integer NA for more). pandas

provides a nullable integer array, which can be used by explicitly requesting

the dtype:

In [14]: pd.Series([1, 2, np.nan, 4], dtype=pd.Int64Dtype())

Out[14]:

0 1

1 2

2 <NA>

3 4

dtype: Int64

Alternatively, the string alias dtype='Int64' (note the capital "I") can be

used.

See Nullable integer data type for more.

Datetimes#

For datetime64[ns] types, NaT represents missing values. This is a pseudo-native

sentinel value that can be represented by NumPy in a singular dtype (datetime64[ns]).

pandas objects provide compatibility between NaT and NaN.

In [15]: df2 = df.copy()

In [16]: df2["timestamp"] = pd.Timestamp("20120101")

In [17]: df2

Out[17]:

one two three four five timestamp

a 0.469112 -0.282863 -1.509059 bar True 2012-01-01

c -1.135632 1.212112 -0.173215 bar False 2012-01-01

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849 bar True 2012-01-01

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804 bar False 2012-01-01

h 0.721555 -0.706771 -1.039575 bar True 2012-01-01

In [18]: df2.loc[["a", "c", "h"], ["one", "timestamp"]] = np.nan

In [19]: df2

Out[19]:

one two three four five timestamp

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059 bar True NaT

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215 bar False NaT

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849 bar True 2012-01-01

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804 bar False 2012-01-01

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575 bar True NaT

In [20]: df2.dtypes.value_counts()

Out[20]:

float64 3

object 1

bool 1

datetime64[ns] 1

dtype: int64

Inserting missing data#

You can insert missing values by simply assigning to containers. The actual missing value used will be chosen based on the dtype.

For example, numeric containers will always use NaN regardless of

the missing value type chosen:

In [21]: s = pd.Series([1, 2, 3])

In [22]: s.loc[0] = None

In [23]: s

Out[23]:

0 NaN

1 2.0

2 3.0

dtype: float64

Likewise, datetime containers will always use NaT.

For object containers, pandas will use the value given:

In [24]: s = pd.Series(["a", "b", "c"])

In [25]: s.loc[0] = None

In [26]: s.loc[1] = np.nan

In [27]: s

Out[27]:

0 None

1 NaN

2 c

dtype: object

Calculations with missing data#

Missing values propagate naturally through arithmetic operations between pandas objects.

In [28]: a

Out[28]:

one two

a NaN -0.282863

c NaN 1.212112

e 0.119209 -1.044236

f -2.104569 -0.494929

h -2.104569 -0.706771

In [29]: b

Out[29]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575

In [30]: a + b

Out[30]:

one three two

a NaN NaN -0.565727

c NaN NaN 2.424224

e 0.238417 NaN -2.088472

f -4.209138 NaN -0.989859

h NaN NaN -1.413542

The descriptive statistics and computational methods discussed in the data structure overview (and listed here and here) are all written to account for missing data. For example:

When summing data, NA (missing) values will be treated as zero.

If the data are all NA, the result will be 0.

Cumulative methods like

cumsum()andcumprod()ignore NA values by default, but preserve them in the resulting arrays. To override this behaviour and include NA values, useskipna=False.

In [31]: df

Out[31]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575

In [32]: df["one"].sum()

Out[32]: -1.9853605075978744

In [33]: df.mean(1)

Out[33]:

a -0.895961

c 0.519449

e -0.595625

f -0.509232

h -0.873173

dtype: float64

In [34]: df.cumsum()

Out[34]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 0.929249 -1.682273

e 0.119209 -0.114987 -2.544122

f -1.985361 -0.609917 -1.472318

h NaN -1.316688 -2.511893

In [35]: df.cumsum(skipna=False)

Out[35]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 0.929249 -1.682273

e NaN -0.114987 -2.544122

f NaN -0.609917 -1.472318

h NaN -1.316688 -2.511893

Sum/prod of empties/nans#

Warning

This behavior is now standard as of v0.22.0 and is consistent with the default in numpy; previously sum/prod of all-NA or empty Series/DataFrames would return NaN.

See v0.22.0 whatsnew for more.

The sum of an empty or all-NA Series or column of a DataFrame is 0.

In [36]: pd.Series([np.nan]).sum()

Out[36]: 0.0

In [37]: pd.Series([], dtype="float64").sum()

Out[37]: 0.0

The product of an empty or all-NA Series or column of a DataFrame is 1.

In [38]: pd.Series([np.nan]).prod()

Out[38]: 1.0

In [39]: pd.Series([], dtype="float64").prod()

Out[39]: 1.0

NA values in GroupBy#

NA groups in GroupBy are automatically excluded. This behavior is consistent with R, for example:

In [40]: df

Out[40]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575

In [41]: df.groupby("one").mean()

Out[41]:

two three

one

-2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804

0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849

See the groupby section here for more information.

Cleaning / filling missing data#

pandas objects are equipped with various data manipulation methods for dealing with missing data.

Filling missing values: fillna#

fillna() can “fill in” NA values with non-NA data in a couple

of ways, which we illustrate:

Replace NA with a scalar value

In [42]: df2

Out[42]:

one two three four five timestamp

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059 bar True NaT

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215 bar False NaT

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849 bar True 2012-01-01

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804 bar False 2012-01-01

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575 bar True NaT

In [43]: df2.fillna(0)

Out[43]:

one two three four five timestamp

a 0.000000 -0.282863 -1.509059 bar True 0

c 0.000000 1.212112 -0.173215 bar False 0

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849 bar True 2012-01-01 00:00:00

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804 bar False 2012-01-01 00:00:00

h 0.000000 -0.706771 -1.039575 bar True 0

In [44]: df2["one"].fillna("missing")

Out[44]:

a missing

c missing

e 0.119209

f -2.104569

h missing

Name: one, dtype: object

Fill gaps forward or backward

Using the same filling arguments as reindexing, we can propagate non-NA values forward or backward:

In [45]: df

Out[45]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575

In [46]: df.fillna(method="pad")

Out[46]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

e 0.119209 -1.044236 -0.861849

f -2.104569 -0.494929 1.071804

h -2.104569 -0.706771 -1.039575

Limit the amount of filling

If we only want consecutive gaps filled up to a certain number of data points,

we can use the limit keyword:

In [47]: df

Out[47]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

e NaN NaN NaN

f NaN NaN NaN

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575

In [48]: df.fillna(method="pad", limit=1)

Out[48]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

e NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

f NaN NaN NaN

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575

To remind you, these are the available filling methods:

Method |

Action |

|---|---|

pad / ffill |

Fill values forward |

bfill / backfill |

Fill values backward |

With time series data, using pad/ffill is extremely common so that the “last known value” is available at every time point.

ffill() is equivalent to fillna(method='ffill')

and bfill() is equivalent to fillna(method='bfill')

Filling with a PandasObject#

You can also fillna using a dict or Series that is alignable. The labels of the dict or index of the Series must match the columns of the frame you wish to fill. The use case of this is to fill a DataFrame with the mean of that column.

In [49]: dff = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(10, 3), columns=list("ABC"))

In [50]: dff.iloc[3:5, 0] = np.nan

In [51]: dff.iloc[4:6, 1] = np.nan

In [52]: dff.iloc[5:8, 2] = np.nan

In [53]: dff

Out[53]:

A B C

0 0.271860 -0.424972 0.567020

1 0.276232 -1.087401 -0.673690

2 0.113648 -1.478427 0.524988

3 NaN 0.577046 -1.715002

4 NaN NaN -1.157892

5 -1.344312 NaN NaN

6 -0.109050 1.643563 NaN

7 0.357021 -0.674600 NaN

8 -0.968914 -1.294524 0.413738

9 0.276662 -0.472035 -0.013960

In [54]: dff.fillna(dff.mean())

Out[54]:

A B C

0 0.271860 -0.424972 0.567020

1 0.276232 -1.087401 -0.673690

2 0.113648 -1.478427 0.524988

3 -0.140857 0.577046 -1.715002

4 -0.140857 -0.401419 -1.157892

5 -1.344312 -0.401419 -0.293543

6 -0.109050 1.643563 -0.293543

7 0.357021 -0.674600 -0.293543

8 -0.968914 -1.294524 0.413738

9 0.276662 -0.472035 -0.013960

In [55]: dff.fillna(dff.mean()["B":"C"])

Out[55]:

A B C

0 0.271860 -0.424972 0.567020

1 0.276232 -1.087401 -0.673690

2 0.113648 -1.478427 0.524988

3 NaN 0.577046 -1.715002

4 NaN -0.401419 -1.157892

5 -1.344312 -0.401419 -0.293543

6 -0.109050 1.643563 -0.293543

7 0.357021 -0.674600 -0.293543

8 -0.968914 -1.294524 0.413738

9 0.276662 -0.472035 -0.013960

Same result as above, but is aligning the ‘fill’ value which is a Series in this case.

In [56]: dff.where(pd.notna(dff), dff.mean(), axis="columns")

Out[56]:

A B C

0 0.271860 -0.424972 0.567020

1 0.276232 -1.087401 -0.673690

2 0.113648 -1.478427 0.524988

3 -0.140857 0.577046 -1.715002

4 -0.140857 -0.401419 -1.157892

5 -1.344312 -0.401419 -0.293543

6 -0.109050 1.643563 -0.293543

7 0.357021 -0.674600 -0.293543

8 -0.968914 -1.294524 0.413738

9 0.276662 -0.472035 -0.013960

Dropping axis labels with missing data: dropna#

You may wish to simply exclude labels from a data set which refer to missing

data. To do this, use dropna():

In [57]: df

Out[57]:

one two three

a NaN -0.282863 -1.509059

c NaN 1.212112 -0.173215

e NaN 0.000000 0.000000

f NaN 0.000000 0.000000

h NaN -0.706771 -1.039575

In [58]: df.dropna(axis=0)

Out[58]:

Empty DataFrame

Columns: [one, two, three]

Index: []

In [59]: df.dropna(axis=1)

Out[59]:

two three

a -0.282863 -1.509059

c 1.212112 -0.173215

e 0.000000 0.000000

f 0.000000 0.000000

h -0.706771 -1.039575

In [60]: df["one"].dropna()

Out[60]: Series([], Name: one, dtype: float64)

An equivalent dropna() is available for Series.

DataFrame.dropna has considerably more options than Series.dropna, which can be

examined in the API.

Interpolation#

Both Series and DataFrame objects have interpolate()

that, by default, performs linear interpolation at missing data points.

In [61]: ts

Out[61]:

2000-01-31 0.469112

2000-02-29 NaN

2000-03-31 NaN

2000-04-28 NaN

2000-05-31 NaN

...

2007-12-31 -6.950267

2008-01-31 -7.904475

2008-02-29 -6.441779

2008-03-31 -8.184940

2008-04-30 -9.011531

Freq: BM, Length: 100, dtype: float64

In [62]: ts.count()

Out[62]: 66

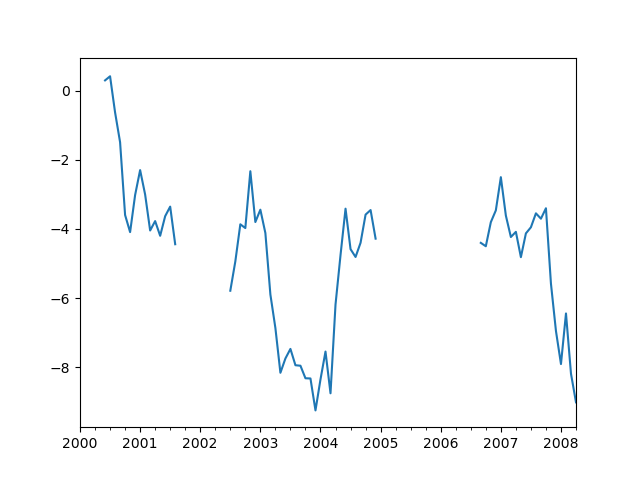

In [63]: ts.plot()

Out[63]: <AxesSubplot: >

In [64]: ts.interpolate()

Out[64]:

2000-01-31 0.469112

2000-02-29 0.434469

2000-03-31 0.399826

2000-04-28 0.365184

2000-05-31 0.330541

...

2007-12-31 -6.950267

2008-01-31 -7.904475

2008-02-29 -6.441779

2008-03-31 -8.184940

2008-04-30 -9.011531

Freq: BM, Length: 100, dtype: float64

In [65]: ts.interpolate().count()

Out[65]: 100

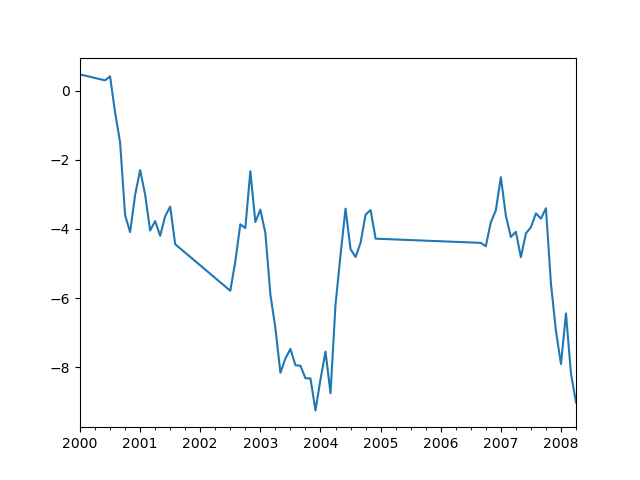

In [66]: ts.interpolate().plot()

Out[66]: <AxesSubplot: >

Index aware interpolation is available via the method keyword:

In [67]: ts2

Out[67]:

2000-01-31 0.469112

2000-02-29 NaN

2002-07-31 -5.785037

2005-01-31 NaN

2008-04-30 -9.011531

dtype: float64

In [68]: ts2.interpolate()

Out[68]:

2000-01-31 0.469112

2000-02-29 -2.657962

2002-07-31 -5.785037

2005-01-31 -7.398284

2008-04-30 -9.011531

dtype: float64

In [69]: ts2.interpolate(method="time")

Out[69]:

2000-01-31 0.469112

2000-02-29 0.270241

2002-07-31 -5.785037

2005-01-31 -7.190866

2008-04-30 -9.011531

dtype: float64

For a floating-point index, use method='values':

In [70]: ser

Out[70]:

0.0 0.0

1.0 NaN

10.0 10.0

dtype: float64

In [71]: ser.interpolate()

Out[71]:

0.0 0.0

1.0 5.0

10.0 10.0

dtype: float64

In [72]: ser.interpolate(method="values")

Out[72]:

0.0 0.0

1.0 1.0

10.0 10.0

dtype: float64

You can also interpolate with a DataFrame:

In [73]: df = pd.DataFrame(

....: {

....: "A": [1, 2.1, np.nan, 4.7, 5.6, 6.8],

....: "B": [0.25, np.nan, np.nan, 4, 12.2, 14.4],

....: }

....: )

....:

In [74]: df

Out[74]:

A B

0 1.0 0.25

1 2.1 NaN

2 NaN NaN

3 4.7 4.00

4 5.6 12.20

5 6.8 14.40

In [75]: df.interpolate()

Out[75]:

A B

0 1.0 0.25

1 2.1 1.50

2 3.4 2.75

3 4.7 4.00

4 5.6 12.20

5 6.8 14.40

The method argument gives access to fancier interpolation methods.

If you have scipy installed, you can pass the name of a 1-d interpolation routine to method.

You’ll want to consult the full scipy interpolation documentation and reference guide for details.

The appropriate interpolation method will depend on the type of data you are working with.

If you are dealing with a time series that is growing at an increasing rate,

method='quadratic'may be appropriate.If you have values approximating a cumulative distribution function, then

method='pchip'should work well.To fill missing values with goal of smooth plotting, consider

method='akima'.

Warning

These methods require scipy.

In [76]: df.interpolate(method="barycentric")

Out[76]:

A B

0 1.00 0.250

1 2.10 -7.660

2 3.53 -4.515

3 4.70 4.000

4 5.60 12.200

5 6.80 14.400

In [77]: df.interpolate(method="pchip")

Out[77]:

A B

0 1.00000 0.250000

1 2.10000 0.672808

2 3.43454 1.928950

3 4.70000 4.000000

4 5.60000 12.200000

5 6.80000 14.400000

In [78]: df.interpolate(method="akima")

Out[78]:

A B

0 1.000000 0.250000

1 2.100000 -0.873316

2 3.406667 0.320034

3 4.700000 4.000000

4 5.600000 12.200000

5 6.800000 14.400000

When interpolating via a polynomial or spline approximation, you must also specify the degree or order of the approximation:

In [79]: df.interpolate(method="spline", order=2)

Out[79]:

A B

0 1.000000 0.250000

1 2.100000 -0.428598

2 3.404545 1.206900

3 4.700000 4.000000

4 5.600000 12.200000

5 6.800000 14.400000

In [80]: df.interpolate(method="polynomial", order=2)

Out[80]:

A B

0 1.000000 0.250000

1 2.100000 -2.703846

2 3.451351 -1.453846

3 4.700000 4.000000

4 5.600000 12.200000

5 6.800000 14.400000

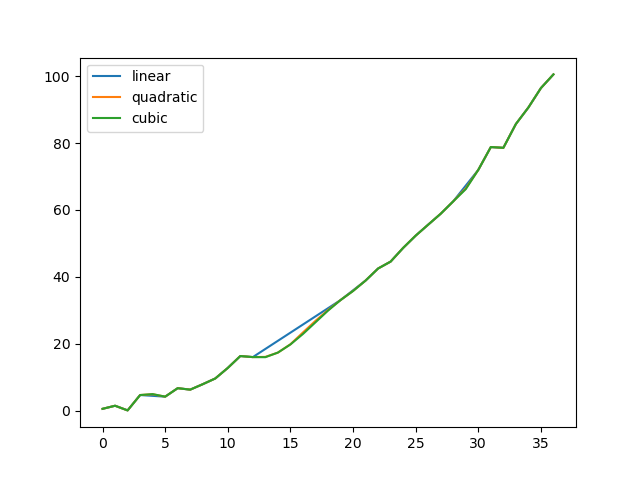

Compare several methods:

In [81]: np.random.seed(2)

In [82]: ser = pd.Series(np.arange(1, 10.1, 0.25) ** 2 + np.random.randn(37))

In [83]: missing = np.array([4, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 29])

In [84]: ser[missing] = np.nan

In [85]: methods = ["linear", "quadratic", "cubic"]

In [86]: df = pd.DataFrame({m: ser.interpolate(method=m) for m in methods})

In [87]: df.plot()

Out[87]: <AxesSubplot: >

Another use case is interpolation at new values.

Suppose you have 100 observations from some distribution. And let’s suppose

that you’re particularly interested in what’s happening around the middle.

You can mix pandas’ reindex and interpolate methods to interpolate

at the new values.

In [88]: ser = pd.Series(np.sort(np.random.uniform(size=100)))

# interpolate at new_index

In [89]: new_index = ser.index.union(pd.Index([49.25, 49.5, 49.75, 50.25, 50.5, 50.75]))

In [90]: interp_s = ser.reindex(new_index).interpolate(method="pchip")

In [91]: interp_s[49:51]

Out[91]:

49.00 0.471410

49.25 0.476841

49.50 0.481780

49.75 0.485998

50.00 0.489266

50.25 0.491814

50.50 0.493995

50.75 0.495763

51.00 0.497074

dtype: float64

Interpolation limits#

Like other pandas fill methods, interpolate() accepts a limit keyword

argument. Use this argument to limit the number of consecutive NaN values

filled since the last valid observation:

In [92]: ser = pd.Series([np.nan, np.nan, 5, np.nan, np.nan, np.nan, 13, np.nan, np.nan])

In [93]: ser

Out[93]:

0 NaN

1 NaN

2 5.0

3 NaN

4 NaN

5 NaN

6 13.0

7 NaN

8 NaN

dtype: float64

# fill all consecutive values in a forward direction

In [94]: ser.interpolate()

Out[94]:

0 NaN

1 NaN

2 5.0

3 7.0

4 9.0

5 11.0

6 13.0

7 13.0

8 13.0

dtype: float64

# fill one consecutive value in a forward direction

In [95]: ser.interpolate(limit=1)

Out[95]:

0 NaN

1 NaN

2 5.0

3 7.0

4 NaN

5 NaN

6 13.0

7 13.0

8 NaN

dtype: float64

By default, NaN values are filled in a forward direction. Use

limit_direction parameter to fill backward or from both directions.

# fill one consecutive value backwards

In [96]: ser.interpolate(limit=1, limit_direction="backward")

Out[96]:

0 NaN

1 5.0

2 5.0

3 NaN

4 NaN

5 11.0

6 13.0

7 NaN

8 NaN

dtype: float64

# fill one consecutive value in both directions

In [97]: ser.interpolate(limit=1, limit_direction="both")

Out[97]:

0 NaN

1 5.0

2 5.0

3 7.0

4 NaN

5 11.0

6 13.0

7 13.0

8 NaN

dtype: float64

# fill all consecutive values in both directions

In [98]: ser.interpolate(limit_direction="both")

Out[98]:

0 5.0

1 5.0

2 5.0

3 7.0

4 9.0

5 11.0

6 13.0

7 13.0

8 13.0

dtype: float64

By default, NaN values are filled whether they are inside (surrounded by)

existing valid values, or outside existing valid values. The limit_area

parameter restricts filling to either inside or outside values.

# fill one consecutive inside value in both directions

In [99]: ser.interpolate(limit_direction="both", limit_area="inside", limit=1)

Out[99]:

0 NaN

1 NaN

2 5.0

3 7.0

4 NaN

5 11.0

6 13.0

7 NaN

8 NaN

dtype: float64

# fill all consecutive outside values backward

In [100]: ser.interpolate(limit_direction="backward", limit_area="outside")

Out[100]:

0 5.0

1 5.0

2 5.0

3 NaN

4 NaN

5 NaN

6 13.0

7 NaN

8 NaN

dtype: float64

# fill all consecutive outside values in both directions

In [101]: ser.interpolate(limit_direction="both", limit_area="outside")

Out[101]:

0 5.0

1 5.0

2 5.0

3 NaN

4 NaN

5 NaN

6 13.0

7 13.0

8 13.0

dtype: float64

Replacing generic values#

Often times we want to replace arbitrary values with other values.

replace() in Series and replace() in DataFrame provides an efficient yet

flexible way to perform such replacements.

For a Series, you can replace a single value or a list of values by another value:

In [102]: ser = pd.Series([0.0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0])

In [103]: ser.replace(0, 5)

Out[103]:

0 5.0

1 1.0

2 2.0

3 3.0

4 4.0

dtype: float64

You can replace a list of values by a list of other values:

In [104]: ser.replace([0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [4, 3, 2, 1, 0])

Out[104]:

0 4.0

1 3.0

2 2.0

3 1.0

4 0.0

dtype: float64

You can also specify a mapping dict:

In [105]: ser.replace({0: 10, 1: 100})

Out[105]:

0 10.0

1 100.0

2 2.0

3 3.0

4 4.0

dtype: float64

For a DataFrame, you can specify individual values by column:

In [106]: df = pd.DataFrame({"a": [0, 1, 2, 3, 4], "b": [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]})

In [107]: df.replace({"a": 0, "b": 5}, 100)

Out[107]:

a b

0 100 100

1 1 6

2 2 7

3 3 8

4 4 9

Instead of replacing with specified values, you can treat all given values as missing and interpolate over them:

In [108]: ser.replace([1, 2, 3], method="pad")

Out[108]:

0 0.0

1 0.0

2 0.0

3 0.0

4 4.0

dtype: float64

String/regular expression replacement#

Note

Python strings prefixed with the r character such as r'hello world'

are so-called “raw” strings. They have different semantics regarding

backslashes than strings without this prefix. Backslashes in raw strings

will be interpreted as an escaped backslash, e.g., r'\' == '\\'. You

should read about them

if this is unclear.

Replace the ‘.’ with NaN (str -> str):

In [109]: d = {"a": list(range(4)), "b": list("ab.."), "c": ["a", "b", np.nan, "d"]}

In [110]: df = pd.DataFrame(d)

In [111]: df.replace(".", np.nan)

Out[111]:

a b c

0 0 a a

1 1 b b

2 2 NaN NaN

3 3 NaN d

Now do it with a regular expression that removes surrounding whitespace (regex -> regex):

In [112]: df.replace(r"\s*\.\s*", np.nan, regex=True)

Out[112]:

a b c

0 0 a a

1 1 b b

2 2 NaN NaN

3 3 NaN d

Replace a few different values (list -> list):

In [113]: df.replace(["a", "."], ["b", np.nan])

Out[113]:

a b c

0 0 b b

1 1 b b

2 2 NaN NaN

3 3 NaN d

list of regex -> list of regex:

In [114]: df.replace([r"\.", r"(a)"], ["dot", r"\1stuff"], regex=True)

Out[114]:

a b c

0 0 astuff astuff

1 1 b b

2 2 dot NaN

3 3 dot d

Only search in column 'b' (dict -> dict):

In [115]: df.replace({"b": "."}, {"b": np.nan})

Out[115]:

a b c

0 0 a a

1 1 b b

2 2 NaN NaN

3 3 NaN d

Same as the previous example, but use a regular expression for searching instead (dict of regex -> dict):

In [116]: df.replace({"b": r"\s*\.\s*"}, {"b": np.nan}, regex=True)

Out[116]:

a b c

0 0 a a

1 1 b b

2 2 NaN NaN

3 3 NaN d

You can pass nested dictionaries of regular expressions that use regex=True:

In [117]: df.replace({"b": {"b": r""}}, regex=True)

Out[117]:

a b c

0 0 a a

1 1 b

2 2 . NaN

3 3 . d

Alternatively, you can pass the nested dictionary like so:

In [118]: df.replace(regex={"b": {r"\s*\.\s*": np.nan}})

Out[118]:

a b c

0 0 a a

1 1 b b

2 2 NaN NaN

3 3 NaN d

You can also use the group of a regular expression match when replacing (dict of regex -> dict of regex), this works for lists as well.

In [119]: df.replace({"b": r"\s*(\.)\s*"}, {"b": r"\1ty"}, regex=True)

Out[119]:

a b c

0 0 a a

1 1 b b

2 2 .ty NaN

3 3 .ty d

You can pass a list of regular expressions, of which those that match will be replaced with a scalar (list of regex -> regex).

In [120]: df.replace([r"\s*\.\s*", r"a|b"], np.nan, regex=True)

Out[120]:

a b c

0 0 NaN NaN

1 1 NaN NaN

2 2 NaN NaN

3 3 NaN d

All of the regular expression examples can also be passed with the

to_replace argument as the regex argument. In this case the value

argument must be passed explicitly by name or regex must be a nested

dictionary. The previous example, in this case, would then be:

In [121]: df.replace(regex=[r"\s*\.\s*", r"a|b"], value=np.nan)

Out[121]:

a b c

0 0 NaN NaN

1 1 NaN NaN

2 2 NaN NaN

3 3 NaN d

This can be convenient if you do not want to pass regex=True every time you

want to use a regular expression.

Note

Anywhere in the above replace examples that you see a regular expression

a compiled regular expression is valid as well.

Numeric replacement#

replace() is similar to fillna().

In [122]: df = pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(10, 2))

In [123]: df[np.random.rand(df.shape[0]) > 0.5] = 1.5

In [124]: df.replace(1.5, np.nan)

Out[124]:

0 1

0 -0.844214 -1.021415

1 0.432396 -0.323580

2 0.423825 0.799180

3 1.262614 0.751965

4 NaN NaN

5 NaN NaN

6 -0.498174 -1.060799

7 0.591667 -0.183257

8 1.019855 -1.482465

9 NaN NaN

Replacing more than one value is possible by passing a list.

In [125]: df00 = df.iloc[0, 0]

In [126]: df.replace([1.5, df00], [np.nan, "a"])

Out[126]:

0 1

0 a -1.021415

1 0.432396 -0.323580

2 0.423825 0.799180

3 1.262614 0.751965

4 NaN NaN

5 NaN NaN

6 -0.498174 -1.060799

7 0.591667 -0.183257

8 1.019855 -1.482465

9 NaN NaN

In [127]: df[1].dtype

Out[127]: dtype('float64')

You can also operate on the DataFrame in place:

In [128]: df.replace(1.5, np.nan, inplace=True)

Missing data casting rules and indexing#

While pandas supports storing arrays of integer and boolean type, these types are not capable of storing missing data. Until we can switch to using a native NA type in NumPy, we’ve established some “casting rules”. When a reindexing operation introduces missing data, the Series will be cast according to the rules introduced in the table below.

data type |

Cast to |

|---|---|

integer |

float |

boolean |

object |

float |

no cast |

object |

no cast |

For example:

In [129]: s = pd.Series(np.random.randn(5), index=[0, 2, 4, 6, 7])

In [130]: s > 0

Out[130]:

0 True

2 True

4 True

6 True

7 True

dtype: bool

In [131]: (s > 0).dtype

Out[131]: dtype('bool')

In [132]: crit = (s > 0).reindex(list(range(8)))

In [133]: crit

Out[133]:

0 True

1 NaN

2 True

3 NaN

4 True

5 NaN

6 True

7 True

dtype: object

In [134]: crit.dtype

Out[134]: dtype('O')

Ordinarily NumPy will complain if you try to use an object array (even if it contains boolean values) instead of a boolean array to get or set values from an ndarray (e.g. selecting values based on some criteria). If a boolean vector contains NAs, an exception will be generated:

In [135]: reindexed = s.reindex(list(range(8))).fillna(0)

In [136]: reindexed[crit]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[136], line 1

----> 1 reindexed[crit]

File ~/work/pandas/pandas/pandas/core/series.py:1002, in Series.__getitem__(self, key)

999 if is_iterator(key):

1000 key = list(key)

-> 1002 if com.is_bool_indexer(key):

1003 key = check_bool_indexer(self.index, key)

1004 key = np.asarray(key, dtype=bool)

File ~/work/pandas/pandas/pandas/core/common.py:135, in is_bool_indexer(key)

131 na_msg = "Cannot mask with non-boolean array containing NA / NaN values"

132 if lib.infer_dtype(key_array) == "boolean" and isna(key_array).any():

133 # Don't raise on e.g. ["A", "B", np.nan], see

134 # test_loc_getitem_list_of_labels_categoricalindex_with_na

--> 135 raise ValueError(na_msg)

136 return False

137 return True

ValueError: Cannot mask with non-boolean array containing NA / NaN values

However, these can be filled in using fillna() and it will work fine:

In [137]: reindexed[crit.fillna(False)]

Out[137]:

0 0.126504

2 0.696198

4 0.697416

6 0.601516

7 0.003659

dtype: float64

In [138]: reindexed[crit.fillna(True)]

Out[138]:

0 0.126504

1 0.000000

2 0.696198

3 0.000000

4 0.697416

5 0.000000

6 0.601516

7 0.003659

dtype: float64

pandas provides a nullable integer dtype, but you must explicitly request it

when creating the series or column. Notice that we use a capital “I” in

the dtype="Int64".

In [139]: s = pd.Series([0, 1, np.nan, 3, 4], dtype="Int64")

In [140]: s

Out[140]:

0 0

1 1

2 <NA>

3 3

4 4

dtype: Int64

See Nullable integer data type for more.

Experimental NA scalar to denote missing values#

Warning

Experimental: the behaviour of pd.NA can still change without warning.

New in version 1.0.0.

Starting from pandas 1.0, an experimental pd.NA value (singleton) is

available to represent scalar missing values. At this moment, it is used in

the nullable integer, boolean and

dedicated string data types as the missing value indicator.

The goal of pd.NA is provide a “missing” indicator that can be used

consistently across data types (instead of np.nan, None or pd.NaT

depending on the data type).

For example, when having missing values in a Series with the nullable integer

dtype, it will use pd.NA:

In [141]: s = pd.Series([1, 2, None], dtype="Int64")

In [142]: s

Out[142]:

0 1

1 2

2 <NA>

dtype: Int64

In [143]: s[2]

Out[143]: <NA>

In [144]: s[2] is pd.NA

Out[144]: True

Currently, pandas does not yet use those data types by default (when creating a DataFrame or Series, or when reading in data), so you need to specify the dtype explicitly. An easy way to convert to those dtypes is explained here.

Propagation in arithmetic and comparison operations#

In general, missing values propagate in operations involving pd.NA. When

one of the operands is unknown, the outcome of the operation is also unknown.

For example, pd.NA propagates in arithmetic operations, similarly to

np.nan:

In [145]: pd.NA + 1

Out[145]: <NA>

In [146]: "a" * pd.NA

Out[146]: <NA>

There are a few special cases when the result is known, even when one of the

operands is NA.

In [147]: pd.NA ** 0

Out[147]: 1

In [148]: 1 ** pd.NA

Out[148]: 1

In equality and comparison operations, pd.NA also propagates. This deviates

from the behaviour of np.nan, where comparisons with np.nan always

return False.

In [149]: pd.NA == 1

Out[149]: <NA>

In [150]: pd.NA == pd.NA

Out[150]: <NA>

In [151]: pd.NA < 2.5

Out[151]: <NA>

To check if a value is equal to pd.NA, the isna() function can be

used:

In [152]: pd.isna(pd.NA)

Out[152]: True

An exception on this basic propagation rule are reductions (such as the mean or the minimum), where pandas defaults to skipping missing values. See above for more.

Logical operations#

For logical operations, pd.NA follows the rules of the

three-valued logic (or

Kleene logic, similarly to R, SQL and Julia). This logic means to only

propagate missing values when it is logically required.

For example, for the logical “or” operation (|), if one of the operands

is True, we already know the result will be True, regardless of the

other value (so regardless the missing value would be True or False).

In this case, pd.NA does not propagate:

In [153]: True | False

Out[153]: True

In [154]: True | pd.NA

Out[154]: True

In [155]: pd.NA | True

Out[155]: True

On the other hand, if one of the operands is False, the result depends

on the value of the other operand. Therefore, in this case pd.NA

propagates:

In [156]: False | True

Out[156]: True

In [157]: False | False

Out[157]: False

In [158]: False | pd.NA

Out[158]: <NA>

The behaviour of the logical “and” operation (&) can be derived using

similar logic (where now pd.NA will not propagate if one of the operands

is already False):

In [159]: False & True

Out[159]: False

In [160]: False & False

Out[160]: False

In [161]: False & pd.NA

Out[161]: False

In [162]: True & True

Out[162]: True

In [163]: True & False

Out[163]: False

In [164]: True & pd.NA

Out[164]: <NA>

NA in a boolean context#

Since the actual value of an NA is unknown, it is ambiguous to convert NA to a boolean value. The following raises an error:

In [165]: bool(pd.NA)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[165], line 1

----> 1 bool(pd.NA)

File ~/work/pandas/pandas/pandas/_libs/missing.pyx:382, in pandas._libs.missing.NAType.__bool__()

TypeError: boolean value of NA is ambiguous

This also means that pd.NA cannot be used in a context where it is

evaluated to a boolean, such as if condition: ... where condition can

potentially be pd.NA. In such cases, isna() can be used to check

for pd.NA or condition being pd.NA can be avoided, for example by

filling missing values beforehand.

A similar situation occurs when using Series or DataFrame objects in if

statements, see Using if/truth statements with pandas.

NumPy ufuncs#

pandas.NA implements NumPy’s __array_ufunc__ protocol. Most ufuncs

work with NA, and generally return NA:

In [166]: np.log(pd.NA)

Out[166]: <NA>

In [167]: np.add(pd.NA, 1)

Out[167]: <NA>

Warning

Currently, ufuncs involving an ndarray and NA will return an

object-dtype filled with NA values.

In [168]: a = np.array([1, 2, 3])

In [169]: np.greater(a, pd.NA)

Out[169]: array([<NA>, <NA>, <NA>], dtype=object)

The return type here may change to return a different array type in the future.

See DataFrame interoperability with NumPy functions for more on ufuncs.

Conversion#

If you have a DataFrame or Series using traditional types that have missing data

represented using np.nan, there are convenience methods

convert_dtypes() in Series and convert_dtypes()

in DataFrame that can convert data to use the newer dtypes for integers, strings and

booleans listed here. This is especially helpful after reading

in data sets when letting the readers such as read_csv() and read_excel()

infer default dtypes.

In this example, while the dtypes of all columns are changed, we show the results for the first 10 columns.

In [170]: bb = pd.read_csv("data/baseball.csv", index_col="id")

In [171]: bb[bb.columns[:10]].dtypes

Out[171]:

player object

year int64

stint int64

team object

lg object

g int64

ab int64

r int64

h int64

X2b int64

dtype: object

In [172]: bbn = bb.convert_dtypes()

In [173]: bbn[bbn.columns[:10]].dtypes

Out[173]:

player string

year Int64

stint Int64

team string

lg string

g Int64

ab Int64

r Int64

h Int64

X2b Int64

dtype: object